east asia as depicted in science fiction animation

or how to avoid orientalist tropes in animation and sci-fi

Notes:

Once again, spoilers ahead for Isle of Dogs and “Good Hunting”, both the short story and TV episode.

Isle of Dogs is available to watch on Disney+ and Good Hunting is available on Netflix via Love Death + Robots.

Science fiction as a genre is not limited to literature, it’s present in almost any type of media we consume, from novels to poetry to movies. In movies specifically, science fiction is conveyed visually, since movies are a visual medium(shocking I know)! Which means that science fiction can be an aesthetic as much as it is a genre.

For example, in a previous essay I analyzed Blade Runner, but we can also expand our examples to include media like Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica. In all of those shows, we can pick out specific imagery that we think make them 'science-fiction’, whether it be space ships, aliens or otherworldly planets etc. The grimy, dilapidated, neon-colored Orientalized setting of 2049 Los Angeles in Blade Runner has set the scene for what many dystopian films or video games would try to emulate in the future. The usage of East Asian imagery and aesthetics in Blade Runner’s setting is especially important as we can see examples of this in real life.

East Asia has also been subject to this ‘aestheticization’, and it has grown in the past few decades, especially with respect to South Korea and Japan since their economies have begun to integrate into global capitalism. Thus, specific cultural and historical artifacts of East Asia(and many other Asian countries) have been reduced down to images and commodities that can be bought and consumed, either as physical objects or through media.

Some questions I will explore are: how does the West(or creators from the West) portray the East in animation? What kinds of power do images hold and how do they inform our perspectives of the world? How does science fiction and techno-orientalism play into that?

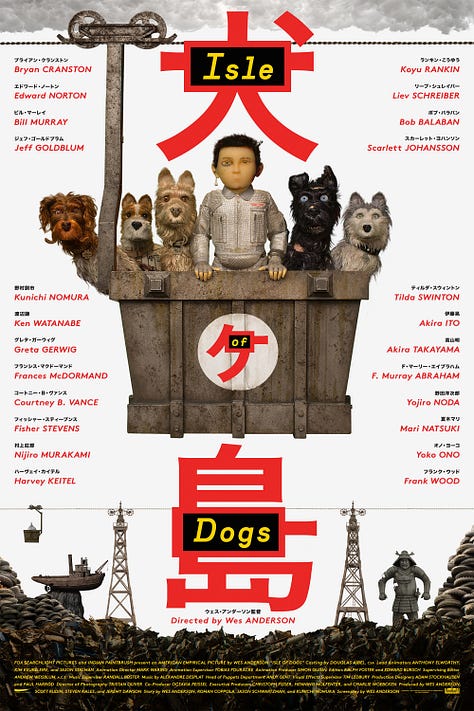

With that in mind, I will be analyzing two pieces of media that encompass the spectrum of how the East can be portrayed in Western media. The first one will be the movie Isle of Dogs from 2018, directed by Wes Anderson, and the second one will be Episode 8 of Volume 1 from the TV anthology Love Death + Robots, titled Good Hunting.

Part 1: Wes Anderson and Depicting the East

When I hear the name Wes Anderson, I picture meticulously crafted arthouse films, expertly constructed composition that frame his eccentric, quirky yet disaffected characters, the majority of whom are white and upper-class. Some of his most popular movies like The Grand Budapest Hotel, Moonrise Kingdom and The Royal Tenenbaums are all characterized as being set in polished postmodern societies with nostalgic narratives.

Of his filmography, he has two animated features: Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, which is one of two of his films that is not set in his usual Upper-East Side setting. The Darjeeling Limited, which features three white brothers who go on a trip to India to “find themselves”, is another movie, similar to Isle of Dogs, where we find modern Orientalist implications in the way the East is framed in the eyes of a Western director.

Isle of Dogs is set in the fictional retro-futuristic Japanese city of Megasaki in the year 2038. There has been an outbreak of the canine flu which threatens the city’s population, so Mayor Kobayashi banishes all dogs to Trash Island off the coast of Japan, including the dog, named Spots, of his nephew Atari. Months later, Atari escapes to Trash Island to rescue Spots and meets a ragtag team of other dogs that assist him in eventually finding a cure for the canine flu.

When I first saw the movie, I was surprised by how unsubtle Japan was portrayed in the animation, setting and musical scoring. Nearly every scene, except for the ones on Trash Island, had some reference to either Japanese cinema, art, culture, architecture or writing systems, even in the credits. However, while I watched the movie, I felt a strange sense of detachment from how Japan was presented to me, the viewer. While the movie showcased numerous aspects of Japanese culture, it was all shown at face value, focusing only on the aesthetic factors it could bring to the movie; something Anderson is very particular about if you watch any of his other films. This essentially renders Japan as a backdrop, filled with a mish-mash of vague references to Japanese culture and art that depicts Japan, and by extension East Asia, as a monolith. We, the viewer, are never taken close enough to view the nuance and humanity of Japan or its people, we are instead presented with a Japan as viewed through the lens of Wes Anderson. Isle of Dogs uses Japan only for aesthetic purposes; it portrays Japan through the eyes of Liberal America, removing the humanity from its culture and reinforcing stereotypical portrayals of Japan.

For example, throughout the movie we are shown clips of sushi making, sumo wrestling, taiko drumming, references to artwork by Hokusai and Hiroshige, Japanese imperial imagery, easter eggs of characters from Kurosawa films and even…mushroom clouds. This is not to say that you cannot portray these images, but you need to do so with intent and precision because images hold power and have history attached to them. The way Anderson presents these images of Japanese culture is extremely sanitized, used only for their aesthetic or visual purposes, which flattens Japan’s history. Perhaps it is because Anderson simply lacks the cultural/historical knowledge that these images hold, and only really views Japan through its exported culture. But I cannot speak for him.

As you can see from the clip above, there is plenty of Japanese dialogue present, but the Japanese characters never really speak. None of the Japanese is officially translated except sometimes through an English speaking interpreter or occasional subtitles. Otherwise, we are just left to interpret the Japanese through expressions and context alone. This omission of consistent subtitles in the movie thus makes us, the audience, empathize more with the white characters and the dogs than we do with the Japanese characters, even though the movie is set in Japan.

Because of this language barrier between the dogs who speak English and the other humans who speak Japanese, the Japanese characters essentially become passive foreigners in their own country. This begs the question of why the movie was set in Japan in the first place? What significance, if any, did the setting have on the story besides its aesthetic values? In an interview about the movie, Anderson says he remembered seeing a sign for a road called the Isle of Dogs in London, and had also wanted to make a movie in Japan, so he and his writers just decided to combine the two. This reasoning is not problematic on its own, but it shows that the movie could have easily been set in any other country, but having it be set in Japan for no other reason other than the fact Anderson wanted to make a movie in Japan shows a lack of care put into accurately representing Japan and its people.

Now, I am not suggesting that Anderson is pushing some kind of techno-orientalist narrative or Western cultural superiority over the East with this movie, but the way he portrays Japan in Isle of Dogs shows another way how the East can be stripped of its history by reducing it down to imagery and aesthetics. Movies like Blade Runner use techno-orientalism to portray the East as a danger to the West, while Isle of Dogs renders Japan and its people as extras in their own country, using techno-orientalist imagery and Japanese aesthetics to flatten Japan, and by extension the East, into a monolith with no real sense of agency.

Part 2: How Ken Liu Writes Sci-Fi Into China

I will now move to analyzing Ken Liu’s short story, titled “Good Hunting”, and its subsequent TV adaptation in the Netflix show, Love Death + Robots. “Good Hunting” is part of a larger collection of short stories written by Liu, serialized in The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories.

“Good Hunting” begins with Liang, the son of a demon hunter in 20th century China, whose father is hunting a hulijing, a fox demon from Chinese mythology that uses her sexuality to lure and steal the vitality of men. Liang saves the hulijing’s pup, whose name is Yan, after his father kills her mother, and their paths crisscross for the rest of the story. Similar to Liu’s other work, “Good Hunting” explores an alternative history narrative where the British occupation of Hong Kong after the Opium Wars leads to the hyper-industrialization of Hong Kong. This introduction of machine and industry results in the suppression of the magic that used to be present in the country, the same kind of magic that allowed Yan to transform into her hulijing form and hunt. The story goes into more detail but I will include a passage that explains what this magic is:

"It is kind of like how a man breathes," the mandarin said, huffing a few times to make sure the Englishman understood. "The land has channels along rivers, hills, ancient roads that carry the energy of qi. It's what gives the villages prosperity and maintains the rare animals and local spirits and household gods. Could you consider shifting the line of the tracks a little, to follow the feng shui masters' suggestions?"

Soon, Liang’s father commits suicide as his job as a demon hunter is no longer viable due to industrialization, but Liang makes the decision to move to Hong Kong, the epicenter of the modernization, in order to survive. In Hong Kong he becomes a talented engineer, while Yan, who has also moved there, has turned to sex work in order to survive. There is no longer any “old” magic left, so Yan is left stuck in her human form, unable to transform into a hulijing. Yan is soon taken by the Governor of Hong Kong’s son, who sexually abuses her and even goes so far as to remove parts of her human body to be replaced with machine. She soon escapes and goes to Liang for help to fully replace her body with automation and create a type of “new” magic that would allow her to transform into a mechanized version of a hulijing and allow her to hunt again.

“Good Hunting” has a mixture of fantasy, sci-fi, mythology and silkpunk genres, as many of Liu’s works do. The story explores themes of anti-colonialism and sexuality through the inclusion of the hulijing. In a blog from Liu about “Good Hunting”, he stated that he wanted to flip the hulijing narrative on its head, shown in the fact that Yan eventually is able to liberate herself from the men that previously abused her, using her sexuality as a source of agency instead of something that was only taken advantage of by men. Liu also thought that the steampunk element could address the “dark stain of colonialism in a satisfactory way”. At one point in the story, where Yan fights back against the Governor’s son who had been sexually abusing her, she says “A terrible thing has been done to me, but I could also be terrible”. This story explores how people of a colonized population learn how to survive under structural oppression and take back power. It provides a nuanced portrayal on anti-colonial violence and revolt by using steampunk elements set during historical events.

The TV adaptation of “Good Hunting” condenses a lot of the short story so it loses some of the nuance and historical/cultural detail that was present in the original story. However, the main themes are still present. I thought the episode did a good job of extrapolating the setting from the short story and didn’t rely strictly on visual aesthetics like Isle of Dogs did. Hong Kong seems to take a lot of inspiration from the silkpunk genre; it’s a mixture of traditional European architecture with Chinese influences like night markets and pagodas, but there is also a retro-futuristic flair shown by the hot air balloons and overall green, blue lighting.

However, in my opinion the TV episode had a lot of unnecessary scenes of nudity and sexual violence, especially with Yan’s character. It read more as a fetishization of Chinese women for the viewer to consume rather than a commentary on it. There were multiple scenes in the episode which showed Yan to be completely nude and certain camera angles that emphasized parts of her body, but not her as a person. She is also often sexualized in situations where she is not in control. Overall, I thought the direction could’ve been handled with more care when exploring Yan’s journey with her sexuality/agency as a Chinese woman without playing so much into the male gaze.

In terms of language, all the characters speak English, but the main voice actors are of Chinese descent. While it would’ve been nice to have the Chinese characters speak Chinese or Cantonese, it makes sense in context to have them speak English when Hong Kong is under British occupation. Unlike in Isle of Dogs, the Asian characters can actually speak for themselves.

So, what makes “Good Hunting” different? I think one way to look at the story is as a response to techno-orientalism, flipping the concept on its head and using it as a metaphor for colonization. Instead of placing the East as the source for industrialization and loss of humanity, “Good Hunting” takes a real historical event, the occupation of Hong Kong by Britain, and uses a techno-orientalist framework to instead portray the West as the source of the industrialization that supplants the humanity of China and its people. The Chinese characters then have to navigate and learn to adapt in order to survive under colonial violence. The use of automation for Yan to regain agency over her body could also be read as a response to the female cyborg body trope, as it is reclaimed as a source of power for Yan.

Similar to Liu’s other works, he often weaves Asian and Asian-American characters or narratives into each story. He doesn’t use Asia as a backdrop or aesthetic and gives depth and nuance to each of his characters; they have motivations and flaws that gives them more humanity and helps us empathize with them, unlike how Isle of Dogs portrays its Japanese characters. Liu uses cultural and historical artifacts from China (like mythology) as a unique plot device or metaphor while still maintaining an emotional core to the story. Perhaps this is because Liu is more familiar with China’s history and understands how to write stories set in China without it falling into Orientalist tropes. This is not to say no white author or director can write stories set in non-Western countries, but it requires more intent and research than just simply relying on tired tropes or aesthetics.

Works Cited:

I would also recommend reading the book Orientalism by Edward Said for a far better breakdown and analysis of Orientalism’s political/cultural implications.

Anderson, Wes, director. Isle of Dogs. Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2018.

Chang, Justin. “Review: Wes Anderson's 'Isle of Dogs' Is Often Captivating, but Cultural Sensitivity Gets Lost in Translation.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 21 Mar. 2018, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-isle-of-dogs-review-20180321-story.html.

Deschanel, Broey, Director. Wes Anderson and the Follies of Modern Orientalism. YouTube, YouTube, 15 July 2020.

Fear, David. “How Do You Solve a Problem like 'Isle of Dogs'?” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 25 June 2018, https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-news/how-do-you-solve-a-problem-like-isle-of-dogs-204452/.

Liu, Ken, and Philip Gelatt. “Good Hunting.” Love Death + Robots, created by Tim Miller, Volume 1, Episode 8, Netflix, 15 Mar. 2019.

Liu, Ken. Paper Menagerie and Other Stories. Head Of Zeus, 2016.

Liu, Ken. “Story Notes: ‘Good Hunting’ in Strange Horizons.” Ken Liu, Writer, 8 Nov. 2012, https://kenliu.name/blog/2012/11/08/story-notes-good-hunting-in-strange-horizons/.